I often find myself preoccupied with a long list of important 21st Century First-World worries. This list includes work, the toddler that lives with us, my wife. DIY and making stuff, the random thoughts that might be fun to ramble on about in this blog, and why can I never find a pen and paper to write down those random thoughts when I have them. Why a post or picture on social media hasn’t had more likes? Why a post or picture on social media has had so many likes? Food.*

Somewhere in that list, I also worry about inefficiency and why other people don’t. That is what I want to talk about today.

*As a quick note, this list is by no means exhausitve and the order is random. Food for example should be much higher.

Before this normal was another normal

The toddler who lives with us (AKA my son) is generally a pretty good sleeper. His bedtime routine is exactly that, routine. Then every so often, when I’ve started to take it for granted, everything is suddenly thrown up in the air and chaos ensues.

My first response is one of panic. I get stressed. My perfectly crafted bedtime regime is ruined! I have no idea what to do now. I have no idea how to navigate my way back to a routine. I have no idea if I even can.

Then my wife patiently says something like this: “You say this every time. And then after a few days everything carries on as normal. Just a little different”

Sneaky change is sneaky

Most people don’t see normal, and most of teh time they can’t see it changing. Like a frog in slowly heated water. Perhaps that is why people are often so unquestioning about the systems they rely on. Or by the complete absence of system or process. It’s crept up on them without them being aware of it.

But, changing things might make things worse!

- Better the devil you know.

- It’s always been that way, and it’s worked up til now. So why would we need to change it?

- People above my pay grade made the decision, so it’s not for me to question.

If they do nothing. They can’t be blamed, right? Things will work themselves out.

Choosing to do nothing is still a decision …

Choosing to continue doing the same thing is still making a decision. Only you are limiting the options (to the thing you already do).

When people fear doing something new, they tend to repeat something familiar. Something safe that’s been good enough in the past. The result tends to be predictable but also derivative. And definitely not innovative.

If I do the same thing things will stay the same, right?

This is a false assumption. That the system will continue in the same way so long as you don’t impart any change on it. But there are factors beyond your control that will impart change and the result is always the same. The balanced system you are relying on will drift out of sync and atrophy.

Failing is scary and normal

It’s also pretty normal to fear failure. We want to succeed. We went to win. We get taught that lesson early on and it gets repeated throughout our lives.

Yet, there are few situations in life where it all comes down to this one try. In most cases, there are other opportunities still ahead. Chances to give it another try. Alternative routes or approaches to take. Competing in the Olympics might be a notable exception to this.

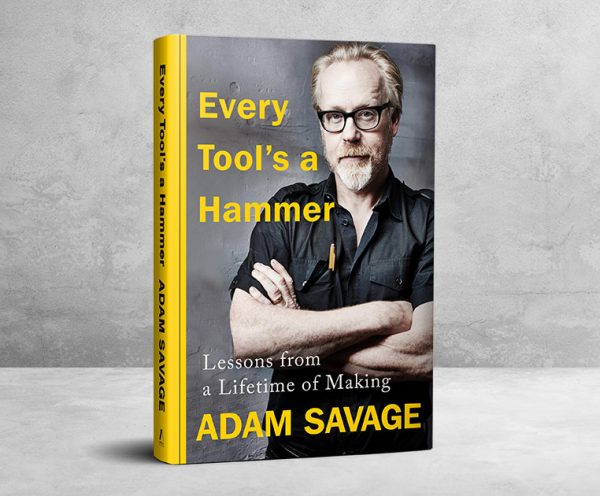

When we say we need to teach kids how to “fail,” we aren’t really telling the full truth. What we mean when we say that is simply that creation is iteration and that we need to give ourselves the room to try things that might not work in the pursuit of something that will. Wrong turns are part of every journey. Adam Savage, Every Tool’s A Hammer

Explore new neighbourhoods

We can analyse and plan ahead of time. We can hypothesise and anticipate all the the known unknowns and challenges we may encounter. We can speculate about the manner and level of unknown unknowns we may also have to tackle. But we can only ever really know by travelling the path ourselves.

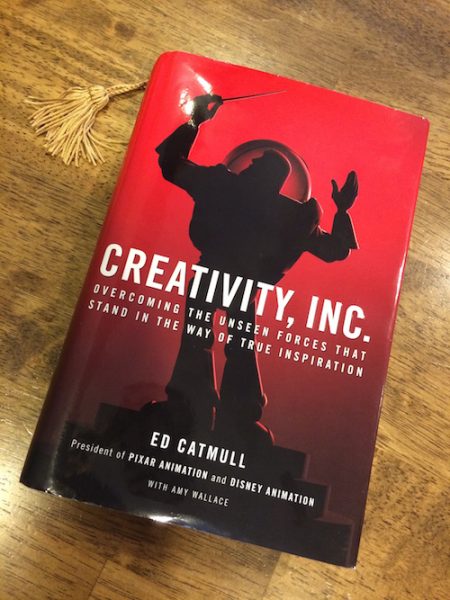

It isn’t enough to pick a path—you must go down it. By doing so, you see things you couldn’t possibly see when you started out; you may not like what you see, some of it may be confusing, but at least you will have, as we like to say, “explored the neighborhood.” The key point here is that even if you decide you’re in the wrong place, there is still time to head toward the right place. And all the thinking you’ve done that led you down that alley was not wasted. Even if most of what you’ve seen doesn’t fit your needs, you inevitably take away ideas that will prove useful. Ed Catmull, Creativity, Inc.

Trial and error is tried and tested

Trial and error / iteration, whatever you want to call it. Has long been recognised by scientists. Construct a hypothesis, test it, analyze and interpret. Take what you now know and let that feed into your next hypothesis. —and then they do it all over again.

Experiments are fact-finding missions that, over time, inch scientists toward greater understanding. That means any outcome is a good outcome, because it yields new information. If your experiment proved your initial theory wrong, better to know it sooner rather than later. Armed with new facts, you can then reframe whatever question you’re asking. Ed Catmull, Creativity, Inc.

Worry less about being wrong and worry more about staying where you are

If you’ve read this far you are probably expecting some sort of conclusion or summary to walk away with. So, here goes.

Stop trying to be right from the start. Stop expecting to nail the details before you begin. Once you accept that you can only know now, what you already know you can make discovery part of the process and start to enjoy rather than fear it. Make choices and test them. Change direction. Create feedback loops. Always be questioning.

Don’t expect change to avoid you or for things to work themselves out if you ignore them. Listen to the new hire asking the naive questions. Because they may offer a fresh perspective and see though the normal you’ve become blind to.